Zarabesque.com

Susti Heaven

Brand Perfect

Closet Nomad

Tiendaholics.com

Ray Harryhausen: Portrait of the Animator as Zeus

by Mark Zimmer

The great stop-motion animator Ray Harryhausen chats with dOc about the new King Kong Collection, his thoughts on CGI, and the dark secret he's keeping from Jennifer Jones.

Legendary animator Ray Harryhausen got his start as an assistant on Mighty Joe Young to equally legendary Willis O'Brien, animator of King Kong. Harryhausen recently spoke to dOc from London regarding the Kong films, Mighty Joe Young, the new Peter Jackson remake and other topics.

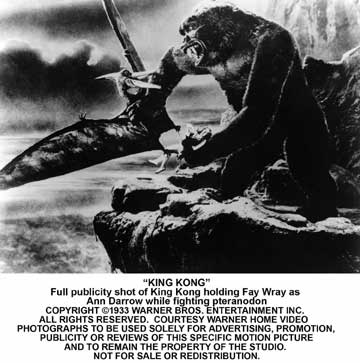

The Premiere of King Kong

dOc: Now, you have a long history with King Kong. What was it like, seeing it for the first time in 1933?

Harryhausen: Oh, that was a revelation. It was amazing how a film can affect somebody at 13. I was 13 or 14 when I saw it at Grauman's Chinese [Theater]. My aunt had worked for Sid Grauman's mother, who was an invalid, and he gave her three tickets to see this film, King Kong, and I knew there was a gorilla in it, but when I got into the foyer at Grauman's, they had this big bust of Kong they used in the film, that moved his teeth, his jaw moved up and down and his eyes rolled and it was quite impressive. Pink flamingos strutting in the foreground. Then when you went inside there was a beautiful stage show that lasted for about an hour, of vaudeville and people in native costumes. To a thirteen-year-old, that was very impressive. Nothing like it has been done since, or anything similar. Whenever Sid Grauman opened a film at his Grauman's Chinese, he would always elaborate on it with a stage show just before the film.

dOc: Did the stage show actually have a connection to the film?

Harryhausen: Oh yes, the native dancers, and it was all in the tradition of a native, South Sea islands vaudeville act. Trapeze performers and costumes based on the native concept. And then the picture came on of course with Max Steiner's great score. It was the first time a film had been completely scored with leitmotifs like an opera. It pushed the film into a different dimension. Talkies had just come in with the early 1930s. In the early days, they used to just use music in the beginning in the end. They used common music that was in the public domain, and sometimes classical scores.

dOc: How many times have you seen King Kong since its original release?

Harryhausen: I've lost count. I think it must be over 200 times.

dOc: Do you have an actual print of it that you studied?

Harryhausen: Oh yes. Now I have the laserdisc, but in the early days you couldn't see it unless you went to a cinema that replayed it on a reissue. Usually they were fleapits. That's how I first met Forry Ackerman and Ray Bradbury, was through King Kong. He also introduced me to Willis O'Brien and Merian C. Cooper.

Kong and The Lost World

dOc: You had seen The Lost World before that, hadn't you?

Harryhausen: I had seen The Lost World when I was a child, about four or five, yes. But it didn't have sound, it had piano music. It was impressive, but it just wasn't the same, you know? I loved the fantasy of it. That stuck in my mind for years, the dinosaurs. My parents tried to explain to me that dinosaurs no longer lived. I didn't know how they were done. But when King Kong came out about ten years later, by the same people, Willis O'Brien and his crew, and Merian Cooper, it was a whole different thing with sound. You had the sound effects of the dinosaurs, and you had the music score that really boosted it. The right type of music, the perfect picture, and the structure of the story was so clever. They took you by the hand from the mundane world into the most outrageous fantasy that's ever been put on the screen. They don't make stories like that any more. The young people seem to be brainwashed by television, and they want some explosions in the first two minutes of the film.

dOc: Right. I think audiences today might not know what to do with a film that takes 45 minutes to get to Kong's island.

Harryhausen: I know. It was the first half hour before you got into the essence of the picture. But that was very cleverly constructed so that you would believe the fantasy when they came aboard.

dOc: At what point did you connect that King Kong and The Lost World were made by the same folks?

Harryhausen: Well, in the museum they had displays of The Lost World and Willis O'Brien, and I noticed the screen credits whenever I saw the film. I was still in high school and I saw a girl in art study class that had a big book that had illustrations of King Kong in it. I couldn't believe it, and I went over afterwards and introduced myself and told her of my interest in stop-motion. Her father had worked for Willis O'Brien at RKO. She said, "Call him up, and he'd be glad to talk to you." Because very few people were interested in stop-motion in the '30s. This was around the '40s. I guess I was unique. He invited me in to see his preparations for War Eagles for MGM, and I was very impressed. It was prepared but it was never photographed.

dOc: Nothing was ever photographed on it?

Harryhausen: There are some photographs and some drawings but it was never completed. The war came along, and Merian Cooper, who was the producer of War Eagles, went into the armed forces, the Flying Tigers. He was a pilot. He lived a fabulous life that's a part of Carl Denham's character.

dOc: There's a pretty strong resemblance between him and Robert Armstrong.

Harryhausen: Yes, I hear apparently they died within hours of each other.

dOc: Between The Lost World and King Kong, the quality of the animation just seems to take a huge leap. Was there a technical improvement there or was it just that O'Brien had a bigger budget to work with?

Harryhausen: Well, he had a better budget and the technical things of course improved, with new experiments. Rear projection was just coming in; they experimented with that a lot on Kong. The Williams traveling matte process was very big in those days, in black and white. It was a means of putting two different pieces of film together to make it look as one. Like the log sequence when Kong was shaking the men off the log, that was made as a test. They used the Williams process, I believe, where they combined the live actors with the animated model.

Assisting O'Brien

dOc: Did you also see The Son of Kong on its theatrical release?

Harryhausen: Yes, later, much later, I saw The Son of Kong. But it was a different picture, it didn't have the qualities Kong had.

dOc: You seem to be pretty disappointed with it.

Harryhausen: Yes, I was. I was very disappointed, because he was so out of character. I think O'Brien was fed up, he didn't like the story and he didn't do much to it. One of his assistants animated most of it. It was sort of clowning around, a comical character making inane gestures. It just wasn't the same as Kong. Kong had a dynamic quality to it.

dOc: You mentioned O'Brien's assistants. How many assistants did he have on King Kong?

Harryhausen: Two or three. He had a whole camera crew, of course. I always worked alone. Animation requires a great deal of concentration, and if somebody asks you the time... I prefer to work alone, so I did all my own camera work. But we had a crew on Mighty Joe Young of about 27 people. We had four matte painters, and we had four projectionists, and two cameramen and an assistant cameraman. It was quite a big operation for about a year.

dOc: How did you end up being assistant to O'Brien?

Harryhausen: Well, he saw some of my work. There weren't many people in those days interested in animation. I was experimenting with fairy tales, and I wanted to make my own dinosaur pictures on 16mm. I showed him some of my work, and when he got ready to make Mighty Joe Young, he chose me for his assistant. It's O'Brien's picture. He planned it and of course contributed to the story and designed all the special effects.

dOc: Was he keeping close supervision over what you were doing?

Harryhausen: I helped him with the preparation when he was making storyboards, so I knew pretty much what would please him. I was so impressed with Kong I knew what he would like. We never had much discussion about it. He would make storyboards and continuity sketches, and I would follow those as close as I could and use my own imagination as well.

dOc: In some of the extras on the DVD, you're seen using some sort of a gauge. What is that, and how do you use it?

Harryhausen: The gauge was something I found very handy. You put it in in between frames when the shutter is closed, and then you know how much you've moved the character. You put it on an ear or on a nose or on a pin on the back of the head, and then you move [the model] slightly, and you can tell how far you've moved it. That's particularly useful if you have slow movements, sometimes a millimeter move for slow action, and for big action you move it about a half an inch or a quarter of an inch. Then you take it out when you expose the film. Then you put it back in and then you know how far you've moved.

dOc: It must have taken a lot of trial and error to learn how to make that movement seem fluid.

Harryhausen: Oh, yes. I experimented on 16mm in my garage for years, trying to make a film called Evolution. By the way, that's out on DVD, with all my early work as well as with the fairy tales I made from '49 on. It's put out by Sparkhill productions. It has when I got my star on Hollywood Boulevard and my Oscar. That's all in the DVD.

Mighty Joe Young

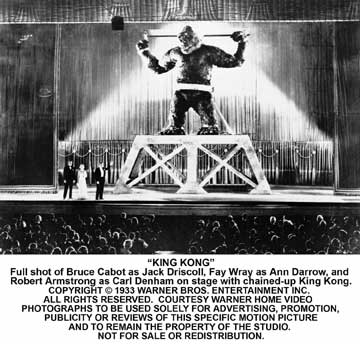

dOc: On Mighty Joe Young, it's always been curious to me why Armstrong was in the movie but not as Carl Denham again.

Harryhausen: Well, he was Max O'Hara. It wasn't supposed to be a sequel. It was a different concept. Mighty Joe wasn't as big as Kong, and he was raised by a girl and he was a kind, nice gorilla. And when they got him drunk, of course, he destroyed the nightclub.

dOc: That nightclub sequence is really amazing. How long did it take to shoot all those pieces and fragments flying around the room?

Harryhausen: They all had to be animated. Some of it we shot at high speed, but when he tore down some of the things I had to animate every piece on a wire, the same as I did on Earth vs. the Flying Saucers, when the Washington Monument fell over after a saucer crashed into it. Each piece had to be animated on a wire. We couldn't afford high speed photography for that at that time. It would take a big crew, so I did it all by myself.

dOc: That's really amazing work.

Harryhausen: I always worked by myself, because I like to concentrate. I prefer not to have people around. So every inch of film is usually the first take. We never had time to do retakes.

dOc: How did you remember from one day to the next, 'Now, was I moving this limb this way or that way?'

Harryhausen: Sometimes if I had to stop a scene I would make notes, but you have it in your mind. When you make storyboards, you sort of think of it as though it's in action. I guess I have a Zeus complex. I like to manipulate these people as Zeus did in the early Greek concepts.

Marcel Delgado and Jennifer Jones

dOc: On Mighty Joe Young, Marcel Delgado was still building the models?

Harryhausen: Yeah. I designed the armatures with Willis O'Brien, and then Marcel was hired to put the flesh on. He made the rubber muscles, and then we covered them with hair. George Lofgren had this process where he rubberized the hair. We used unborn calf hair on the models so they were in proportion.

dOc: One doesn't hear a lot about Delgado. Do you have any recollections about him in particular?

Harryhausen: Oh, he was a very clever man. He did a lot on Kong. He did all the dinosaurs. Willis O'Brien would design them, and then Marcel would build them, which takes a lot of time. He did all the models on Kong, and then did the models for us on Mighty Joe. His brother Victor worked with him as well.

dOc: Did Jennifer Jones ever find out that you had named the ape model after her?

Harryhausen: No. I hope not. I think that she wouldn't be very flattered. It was sort of a joke at the time, because Lust in the Dust—what was it?—Duel in the Sun, with Gregory Peck and Jennifer Jones, they were just making that. Sometimes when our rushes came in, we'd have to wait until they'd finished their rushes to see our rushes. I saw the little scene where they were shooting at each other and little Jennifer Jones' quivering hand came up on the rock. We had four models, so I named my model Jennifer! I hope she never finds out.

dOc: On the commentary for Mighty Joe Young, you mention that the finale with the fire was in Technicolor at one point?

Harryhausen: Yes, we were going to shoot it in Technicolor at one time, but the budget was too high so they had to cut it down. On the early release prints, Technicolor injected the color. It wasn't shot in color. It was shot in black and white and Technicolor had a process of putting in the red flames and the yellow flames in some way in the black-and-white print. But most prints don't have that now. Only the first release.

dOc: Do you know if any of those still survive?

Harryhausen: There is one that's colored all red, and it's not the same. I don't know whether they've survived. Perhaps someone has some somewhere, maybe the Academy or the BFI. You seldom see it with the color in the last reel.

Aspect Ratios and Kong on the Big Screen

dOc: Now, when you were shooting your effects for your later films, were those still shot in Academy ratio?

Harryhausen: We shot them in full aperture for television, and 1.85 for showings in the cinemas.

dOc: So you'd film it twice?

Harryhausen: No, we would just allow the headroom so when it went on television the heads wouldn't be cut off. Sometimes half the picture is cut off when they show it on 1.85. It cuts down the size of the picture.

dOc: But they were primarily meant to be shown widescreen?

Harryhausen: Yes, during the widescreen period, and you also had to keep the Academy aperture open for showings on television.

dOc: Have you had a chance to see Peter Jackson's re-creation of the spider pit sequence?

Harryhausen: No, I haven't. He invited me down to do a cameo in the new film but I couldn't leave London because I have a commitment to sign books. So I had to turn him down. He flew my wife and I down there to New Zealand several years ago, and we saw the models when he was going to do Kong as animation. Then the picture was canceled and then they took up The Lord of the Rings. But now he's going to do everything on CGI. He won't use models. He loves the film as much as I do, and I know he'll do a good job. It'll be an interpretation. It probably won't be exactly like the original.

But it's very hard to capture that quality that was in the '30s, the naïve quality. Everybody's so jaded today, everybody wants to be a critic, you know. So it's not what it used to be. When I grew up we waited Saturday evenings to see the latest wonderful film at the local cinema, and it's not the same today. You're inundated with films. Bars and television and sick films and home theaters. People are calloused about entertainment, I think. One successful film comes out and then everyone wants the next one to be a little more successful, so they put more explosions in it. It's just not the same as it used to be. I hope you had seen Kong on the big screen for the first time, it's not the same as when you see it on a little box.

dOc: No, I don't believe it is.

Harryhausen: You have to see it on a big screen. It's made for somebody to look up to, not to look down to.

dOc: The prints I've seen of it on a big screen have always been lousy, so it'd be nice if this restored version eould go out in theaters.

Harryhausen: They probably could release this restored version on DVD in theaters. We just got back from Nantes, in France, and they showed Mysterious Island, and it was on a disc. And the quality was superb.

On CGI

dOc: Have you seen any footage from Peter Jackson's version?

Harryhausen: Just on the coming attractions reel that was on public television. It'll be his concept and his interpretation. The 1975 Kong left all the fantasy out. Peter Jackson has put the fantasy back. He loves the original film as much as I do, so it'll be a fascinating interpretation, but there'll only be just one King Kong.

dOc: What are your thoughts on computer graphics having displaced the stop-motion animation business?

Harryhausen: Well, that's the modern concept. I think there's room for every medium depending on the story told. One of the things that fascinated me was that stop-motion added this nightmare quality. You knew it wasn't real, and yet it looked real. You knew it wasn't a man in a suit, but you didn't quite know how it was done. That was the fascinating part of it. It was like a nightmare quality. If you make things too real, you defeat the fantasy of it and bring it down to the mundane. That's my theory.

dOc: So you wouldn't have used CGI in the '60s or '70s if it had been available to you?

Harryhausen: No. Because I grew up the other way. Some animators today use frame grabbers, they have a television thing on the side of the camera, or through the camera, and they can see on the screen instantly what they're animating. They can go back and refine it and refine it. I always liked to just wait till the next day and see what I'd caught on the screen.

dOc: There must have been some surprises that way.

Harryhausen: Very much so! I've done fifteen feature films, and every inch of animation I did myself. I always worked alone. I animated, lighted, set the miniatures, set up the rear projection, because I didn't want to work with a crew. I found that it wasn't satisfying. Today, they have 80 people doing what I did! Of course, they turn things out by industrial process, so I guess they need them.

![]()